#07 - Thuya

Carving Cedar: Gus sends a timeless greeting from a Maine garden

Cathy Jewitt, Author

John T. Meader, Photo & Content Editor

When I was little, I often visited my grandparents in Asticou, which is part of the village of Northeast Harbor, Maine. In the evenings, often we would walk to a secluded and magical place. Following a path that led us through the woods and up Asticou Hill, we entered Thuya Garden.

Thuya Garden, 2021, photos by John Meader.

(Click on any photo throughout the post to enlarge.)

Many decades have passed since we took those evening walks. Now I am a docent at the garden’s Thuya Lodge. I welcome visitors who come to explore the historic house and hillside garden. Their delight at what they find here is something my heart understands. We share joy engendered by the labor of those who preserve and maintain Thuya today. We feel gratitude for those whose vision and hard work over the past century has culminated in this island refuge. Indeed, the past is present here, and we are invited to share it.

Gardeners tend the plants while visitors explore the grounds, photo by John Meader.

The American writer Annie Proulx understood this simultaneity, this past/present awareness, when she wrote in her novel Postcards that “the laborers’ vision and strength persists after the labor is done.”^1 Sustaining a property like Thuya asks for a paradoxical approach. Preserving both the intangible and tangible efforts of those whose previous contributions created this place is essential. Thuya’s contemporary caretakers ensure the past remains, often using modern practices to solve problems that arise. Change ensures the original inheres.

The following quote from architect Peter Zumthor, whose own works are frequently described as timeless, gives us a glimpse into the desire to create spaces that sustain us.

Every time I imagine a garden in an architectural setting, it turns into a magical place. I think of gardens I have seen, that I believe I have seen, that I long to see, surrounded by simple walls, columns, arcades or the facades of buildings – sheltered places of great intimacy where I want to stay for a long time.^2 —Peter Zumthor

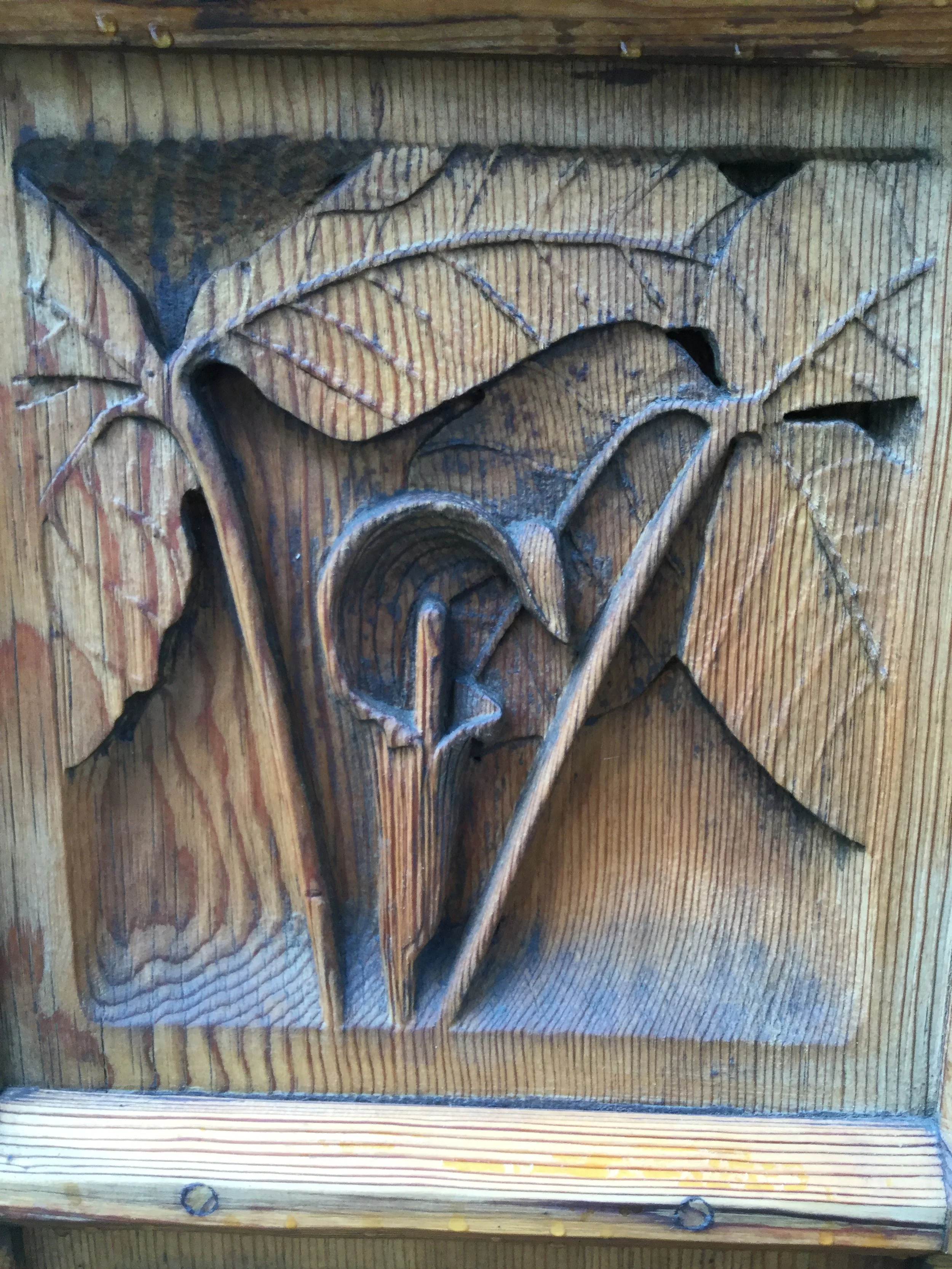

How does Gus’s story take us to this secret garden tucked into a hillside on Mount Desert Island? As one of the laborers who constructed Thuya’s simple walls, Gus and other workers made landscape designer Charles Savage’s sketches for a fence surrounding the garden a reality.^3 The fence would be both artistic and practical—hungry deer must be kept out and visitors invited in. Two large entrance gates carved from local cedar would welcome visitors. Designed by Savage, they were carved and constructed by Gus.

Cedar fences and gates, photos by John Meader.

The story of Thuya's history begins in 1880—eighty-two years before Gus carved the gates—when Bostonian and rusticator Joseph Curtis (1841-1928) traveled to Asticou. A landscape gardener, Curtis discovered woods populated with pines, cedars (Thuya occidentalis), and lichen and moss-covered granite outcroppings on the side of Asticou Hill (now Eliot Mountain). The congenial company of nearby local islanders, as well as conversations and hikes with friends from Boston who also were discovering the rustic beauty of Mount Desert Island, awoke his desire to spend more time on that hillside. He purchased land there.

Captain Augustus Savage, “Savage Genealogy” photo.^4

Having completed studies in landscape design and civil engineering, as well as service in the Civil War, Joseph Curtis planned the first house he’d build on his new property. A man of comparatively modest means and unpretentious tastes, Curtis differed from some of his wealthy contemporaries who were building enormous summer cottages on the island, many of them in Eden (now Bar Harbor). Asticou, on the other hand, was attracting artists and intellectuals seeking a less ostentatious lifestyle.

Curtis, in his early forties and not yet married, decided a log cabin would suit his needs. He asked Captain Augustus Savage, a local resident from whom he had rented rooms in Asticou, to build it. The cabin, completed in 1881, was the first of four dwellings Curtis owned on the property. Curtis and Savage became friends. This association between residents, one year-round and the other seasonal, would result many years later in Curtis’s friendship with Captain Savage's grandson Charles.

Thuya Lodge 2021, photos by John Meader.

By the early 1900s, Curtis’s intimate knowledge of the hillside had prompted him to apply his design and engineering skills there. Married now, with a wife and son, he sited Thuya Lodge to capture both stunning water views and cooling summer breezes. He planted a small orchard and discovered a spring that provided water for the house. He designed and oversaw construction of the Asticou Terraces—a path with a series of granite steps that wound down the hillside to the road (Peabody Drive) and ultimately led to Asticou Landing on the harbor. Today, visitors often park just off Peabody Drive and walk the quarter mile path up the hillside, frequently stopping to admire the views and rest in the rustic lookouts that Curtis nestled into the landscape.^5

Asticou Terraces footpath, photo by John Meader, 2021.

Gus’s Postcard of one of the Asticou Terrace shelters in winter at sunset,

circa 1968.

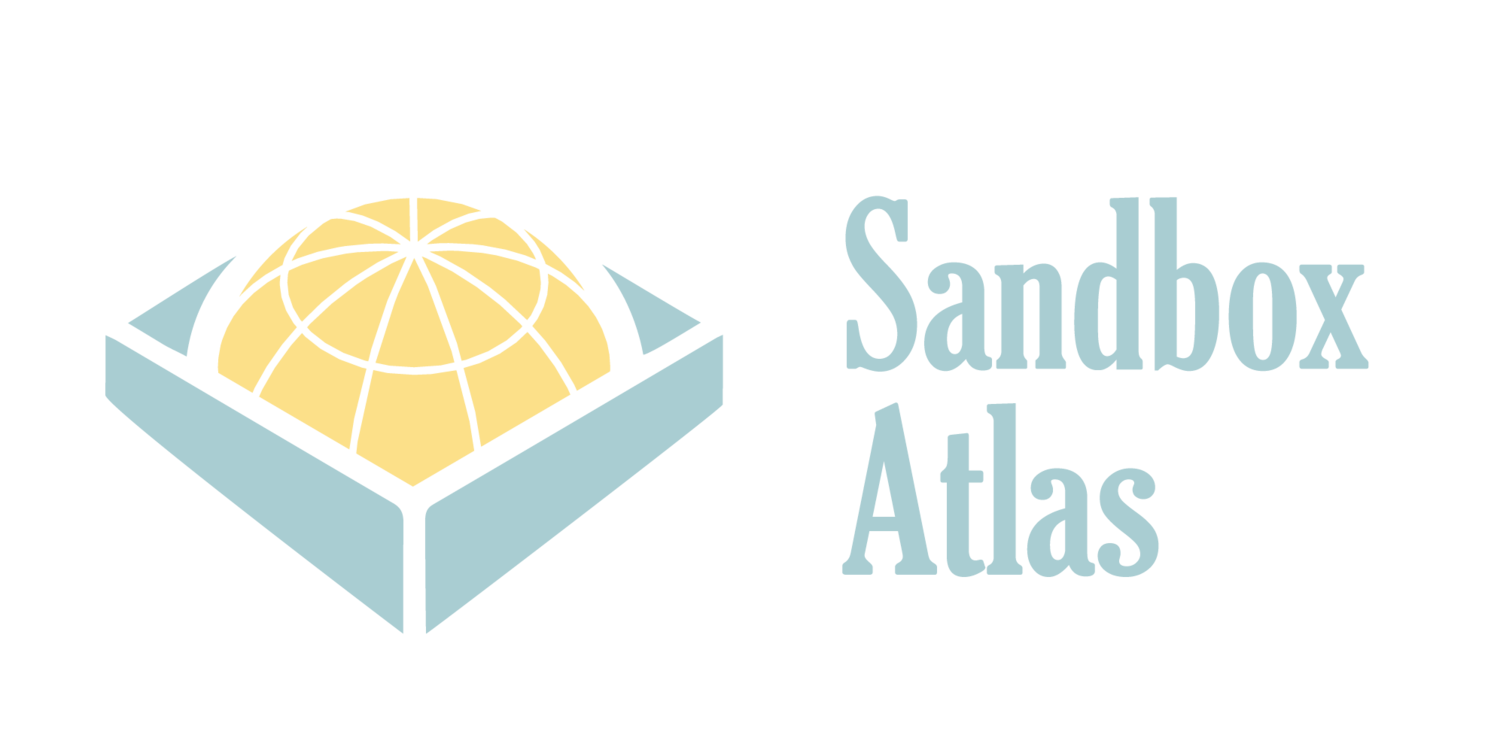

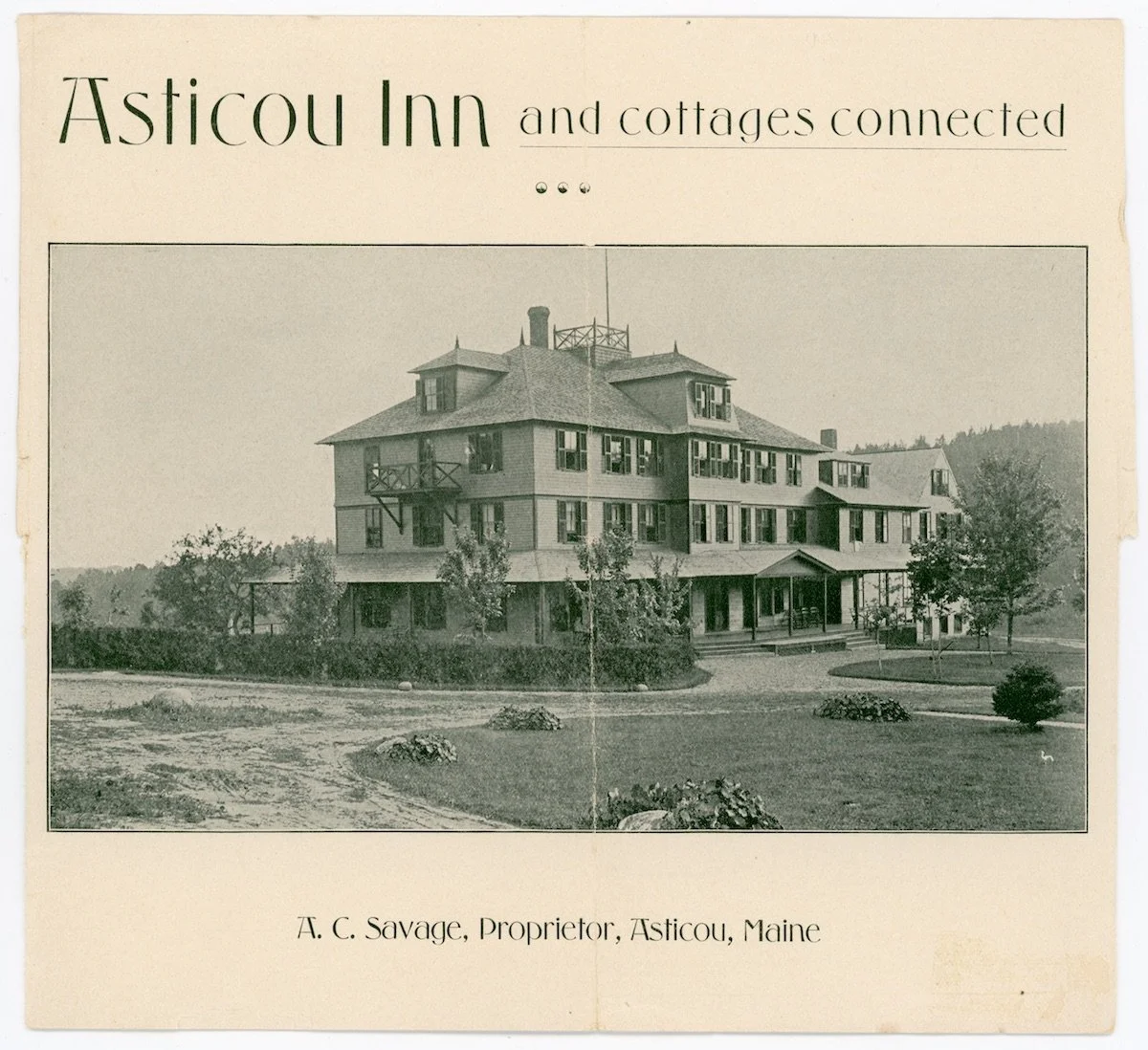

For Curtis, the Terraces also served a practical purpose, that of providing the shortest way down Asticou Hill to enjoy dinner with friends in the neighborhood. Sadly, Curtis’s wife Amelie died in 1913, so he was accompanied only by his son Henry. Often, he ate at the Asticou Inn, but sometimes he visited Gus’s parents Fred and Cora Phillips. Fred had married Captain Savage’s daughter Cora Justina in 1888. The Phillips family lived across from the Inn in a cottage designed and built for them as a wedding gift by Cora’s younger brother, the architect Fred Savage.

Advertising brochure for the Asticou Inn and Cottages, circa 1880’s, courtesy of Northeast Harbor Library.

Gus would have been in his late teens then, home for the summers but returning to Hebron Academy for the school year. Was he at the dinners that his older sister Emily describes in her diary? She doesn’t mention which of her brothers and sisters were present, but remembers the Curtises visiting the Phillips house (aka Phillips Cottage): “Sometimes in the fall Mr. Curtis and his son Henry used to come up to our house for their suppers. They liked my mother’s cooking and said so. I was around and helped what I could.”^6 Fresh venison, fish hash, and clam chowder, along with her homemade baked goods, were some of Cora’s favored dishes.

Joseph Curtis with one of his walking sticks, photo courtesy of Northeast Harbor Library.

Curtis’s collection of walking sticks, preserved at Thuya Lodge, conjures up the vision of a trim, bespeckled man and his son navigating the path up Asticou Hill after a home cooked meal, perhaps fish hash or a good chowder, and holding small lanterns to light their way. Curtis’s son Henry predeceased him in 1918.

From those first years on Mount Desert Island (MDI) until his health declined in the mid-1920s, Curtis enthusiastically embraced his time spent on MDI. An energetic and talented man, he worked on clients’ design projects, wrote articles and books, and furthered his vision for his hillside retreat. Curtis died on May 27, 1928, leaving the management of the estate in the hands of Charles Savage.

Several years before he died, Curtis had asked Charles to be the sole trustee of the Asticou Terraces Trust after his death. Ownership of his estate would go to the town of Mount Desert and Charles would manage the trust, preserving the property, trails, and Curtis's final home, the arts-and-crafts-style cottage named Thuya Lodge. Per Curtis’s wishes, Charles would open them all for visitors to enjoy in 1931.^7

Charles Savage was twenty-five years old when he began to carry out Curtis’s wishes. During the three years between Curtis’s death and the opening of the Lodge, the rustic simplicity and arts-and-crafts-style interior of the Lodge were carefully preserved. With establishing a library in the upstairs rooms in mind Savage began collecting rare books on botany and landscape design.

Looking towards the Asticou Inn from the Asticou Terraces,

photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum.

During the 1930s and 40s, visitors to Thuya Lodge walked up the Asticou Terraces, often pausing, as Curtis intended, to rest in one of the rustic shelters and take in the harbor view. Arriving at the Lodge, they were greeted by a hostess who welcomed them in for conversation and tea. Sometimes the hostess, like Gus’s future daughter-in-law (the author’s mother), worked at the Asticou Inn in the mornings and at the Lodge in the afternoons. Before guests left, the hostess would invite them to sign the guest book.

In the early 1950s, Savage hired local workers to convert the upstairs bedrooms into a botanical library. He envisioned a comfortable space for visitors who wished to read and research. With help from friends and summer residents, Savage had collected both rare and contemporary books on botany, horticulture, and landscape design. By 1954 the new library was open and visitors were welcomed upstairs for the first time.

After more than ninety years, today’s docents carry on many of these traditions. Visitors are invited to explore the house and library, and to examine the simple, yet comfortable, furnishings and construction details, such as the several fireplaces that would have kept Curtis and Henry comfortable on chilly evenings. “Do you let people stay overnight here?” is a common question the docents are asked. “No, unfortunately not.” It wasn’t until the late 1950s that Thuya Garden was created.^8

Beatrix Farrand’s Reef Point Gardens in Bar Harbor, Maine, 1920. Glass lantern slides, hand colored. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.^9 & 10

Beatrix Farrand, courtesy of UC Berkeley, Environmental Design Archives^11.

Charles Savage walking in the woods, 1949,

photo courtesy Maine Memory Network.^13

In one of life's unexpected turns, the dismantling of Beatrix Farrand’s Reef Point Gardens in Bar Harbor was the catalyst for the physical creation of Charles Savage’s Thuya Garden. Farrand, a practicing landscape architect, had envisioned sharing her seaside specimens with students interested in garden design. She would teach them, for example, which Rhododendrons were suited to Maine’s cold winters and how both tall and dwarf White Spruces were striking elements integrated into a designed landscape. Her plans abruptly changed in the mid-1950s. She chose to demolish her gardens, but her years of experimentation and labor would not be lost. When Savage, not only a gifted and largely self-taught landscape designer but also a Reef Point board member, heard about her decision, he was determined to salvage Farrand’s plants. He would find a home for them in Asticou, integrating them into two new gardens he already had in mind. One of them was Thuya Garden (the other was Asticou Azalea Garden). Soon hundreds of Farrand’s specimens, bought with Savages’s own money and the financial assistance of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., were dug up at Reef Point and transported to Asticou by his cousin Gus Phillips and other local workers.^12

Savage had been considering garden designs for the Thuya property for years, rendering some of the details in color sketches. He envisioned a small English border-style garden at home in Thuya’s natural surroundings. Just as Curtis had integrated rustic lookouts into the hillside Terraces years earlier, Savage designed simple shelters with comfortable seating for the new garden. Curtis’s spring would be protected by a wellhouse pavilion.

As work on the garden commenced, Savage knew he must protect the plants from the deer that roamed Asticou. He made detailed sketches for a tall cedar fence that would surround the new garden. Knowing his cousin and neighbor Gus Phillips was a skilled carpenter, he hired Gus to build the fence. Gus’s notebooks record his hours spent locating cedar trees on the property, having them cut and milled, and finally building the fence. Soon he was also building the garden shelters and constructing the pavilion over the spring. But his most challenging project was still on the drawing board. ^14

Gus’s Postcard #90 of Thuya Gates, designed by Charles Savage, carved and built by Augustus “Gus” Phillips.

Photo courtesy of “Savage Genealogy”^15

It was Savage’s vision for a pair of large cedar gates with hand-carved panels that gave Gus the opportunity to demonstrate more than his talent for carpentry. The cousins discussed the individual panel designs—twenty-four for each gate. Almost all would depict a local plant or animal—a fiddlehead, a jack-in-the-pulpit, a rabbit, a frog, etc. Visitors to the garden would be greeted by an entrance that was both functional and artistic. Gus agreed to take on the carving project and the construction of the gates that would house the panels. Savage would carve two additional larger panels out of mahogany to identify Thuya Garden and Thuya Lodge. All fifty panels would be set into the gates. As Gus carved away in his workshop, many relatives and friends found excuses to seek him out there. Crossing the threshold into the shop, they were greeted by the spicy sweet fragrance of cedar shavings and chips. Lingering became a habit.

The Phillips House that was rented out each summer, photo by John Meader.

By the early 1960s, Gus was carving the gates’ panels. As an owl, a rabbit, a pitcher plant and more were coming to life, Gus found himself burdened with many other responsibilities and little time for rest. He, and his wife Mary, also worked part-time for their Savage relatives who owned the Asticou Inn. Gus often took on carpentry projects for summer neighbors. A significant part of their yearly income was derived from renting out their large, shingle-style house for the summer season. Each spring they moved into their small house located behind the Phillips House. When their 5 children were young, the family’s vegetable farm truck carried their belongings to the little house. By the 1960s, Gus’s Rambler made the trips back and forth. During the summer days, Mary donned her gray uniform and starched white apron and walked to her own big house, where she spent the day as the housekeeper for the family that rented there. On top of all this, Mary and Gus were caring for Mary’s elderly and ailing mother who now lived with them. The year 1960 ended with the death of Gus’s brother Luther on Christmas Eve.

Gus promoting his maps, courtesy the author’s collection.

Note Gus’s painted mural of an aerial view of Mount Desert Island and the Coast of Maine.

Gus inherited Luther’s Phillips Map and Postcard business, which he had been assisting with as time allowed. After studying Luther’s sales books, Gus saw to the delivery of Luther’s unfilled orders and the filling of new ones. Quickly, Luther’s business became Gus’s business. He not only filled Luther’s orders for maps and postcards, but he soon was making his own maps and shooting his own postcards. As often happens, just when one thinks his or her life couldn’t become any busier or more stressful, it does. This proved true for Gus.

Gus’s camera,^16

photo by John Meader.

By the time Thuya Garden opened its gates to the public in 1962, Gus was steadily engaged in running the variety of jobs that his postcard and map business required. With his camera, he explored the state, taking his own images. He spent winter evenings choosing which photos to turn into postcards. Inspired by his late brother’s pictorial cartography, he had begun to create his own maps. Over the next several years, Gus’s mapmaking would evolve as his love for painting landscapes and emerging techniques in printing influenced his cartography and resulted in a unique series of maps. In 1963, Gus published his map of Swans Island.

Early color rendition of Gus’s first map of Swans Island, Maine, 1963, courtesy of the author’s collection.

As word spread of his artistic abilities, only a year later the Northeast Harbor Village Improvement Society asked if he would make a specialized Mount Desert Island map. He agreed to “recreate a revised map of the island trail system based on Turner’s 1941 Joint Path Committee maps.” Gus’s map was soon declared “the first complete map since Turner’s 1941 map.” The Olmsted Center’s Cultural Landscape Report for the Historic Hiking System of Mount Desert Island states, in part “The park service produced maps in the 1950’s, ’60s, and ‘70s, but without topography they were inferior to those produced by the AMC and Augustus Phillips.” That map has been revised and republished many times. ^17

Path and road maps of Mount Desert Island, 1975 edition, by Augustus “Gus” Phillips, courtesy Northeast Harbor Library.

In the 1960s, Mount Desert Island’s population increased more dramatically each summer season. In 1968, Acadia National Park recorded 2,303,300 visitors.^18 Although the island’s Gilded Age was now a memory, the descendants of earlier rusticators and cottagers continued to return for the season and maintained friendships with many of the island’s year-round residents. At the same time, a boom in tourism led to vacationers booking shorter stays at motels with names like The National Park, The Sunny Side, and The Anchorage.^19 A new generation of seasonal residents began renovating some of the historic cottages and secured land for new houses. Gus found these tourists eager to buy postcards and maps.

Three of Gus’s Post Cards of Mount Desert Island and Acadia National Park

Local businesses, as well as the Acadia Corporation that services the national park, kept Gus hopping as he delivered their orders for thousands of postcards and hundreds of maps. Frequently, he recorded sales to local and seasonal residents. Among them was Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison, a summertime neighbor in Northeast Harbor. Morison, a Harvard historian and Pulitzer Prize winning author wrote many books, including The Story of Mount Desert Island. He placed an order for 3,000 postcards.

By this time Gus had photographed Thuya’s gates and parts of the garden and terraces. He had the images published as postcards. Gus’s recorded sales indicate that the Thuya shots were popular. Because his jumbo-size postcards of Hebron Academy had sold well, he had both regular and jumbo-sized cards of Thuya’s hand-carved gates printed. Another postcard shows a visitor admiring one of the summer border garden beds. The woman is Gus’s wife Mary. Gus continued his practice of including his wife in a photo whenever she would acquiesce. One can just hear her saying, “‘Gustus, be quick! I’ve got work to do.”

Gus’s postcards of Thuya Garden and environs from the late 1960’s compared to John’s similar photographs from 2021.

Ever since Joseph Curtis tended his hillside acres over 100 years ago, caretakers have preserved what makes Thuya, well, Thuya. It is the dedication of those who keep returning to this place, as well as the delight of those who discover it for the first time—as visionaries, as laborers, as visitors—that elevates Thuya from an ordinary to an extraordinary landscape. Maintaining Thuya requires the labor of a gifted, creative group of caring individuals. At Thuya it’s easy to step away from our busy lives for a few minutes or, as Peter Zumthor says, “stay for a very long time.” One more greeting from Gus can be read by visitors before they step into Thuya Lodge. To the left of the entrance door is a large map with an overview of the Thuya property that he completed in 1973.

Photographer’s Notes—John T. Meader

In the summer of 2021 I visited Thuya Garden and Lodge for the first time. Winding up the narrow road that climbs the hillside from Peabody Drive I marveled at the beautiful forest of cedars and pines growing between ledge outcrops highlighted with lichens and mosses. It’s easy to see why Joseph Curtis was enthralled by this landscape, it draws you in. My approach at shooting the garden on that warm August day was threefold. First, I wanted to recreate Gus’s shots from the 1960’s to see how the garden compares to what Gas saw through his lens nearly 60 years ago. Second, I wanted to capture the craftsmanship of the lodge, fences, and gates, many of which Gus had a hand in creating. Finally I wanted to study the delicate balance of colors and forms created by the blossoms and plants so carefully maintained by today’s skilled and knowledgeable gardeners. The images throughout this entry will hopefully give a visual sense of the dedication and hard work required to maintain this garden which was first conceived in the mind of Charles Savage many years ago.

Photos by John Meader, 2021.

Apple Tree, photo by Cathy Jewitt.

One of Curtis’s original apple trees still grows in Thuya Garden. It’s a testament, perhaps, to those whose vision, labor, and imagination were the seeds that brought this hillside terrain to fruition.

Special Thanks:

The Penobscot Marine Museum and Photo Archivist Kevin Johnson for preserving The Phillips Collection and continued support. At Thuya: Garden Manager Rick LeDuc, Head Gardener Wendy Dolliver, Lead Groundskeeper Jason Ashur, Woodland Gardener Margaret Handville, Gardener Eddie, Docents Helen Townsend and Linda Thayer, and retired Docent Ellen Gilmore. The Land and Garden Preserve for stewardship of this and other Preserve properties. The Northeast Harbor Library for permission to use archival material. The Bar Harbor Historical Society and Debbie Dyer, Historian, for permission to photograph Gus’s cameras and a fascinating tour of La Rochelle. Mary Jane Phillips Smith for memories, stories, and artifacts preserved and shared. Pamela Dean, Phd, project scholar. Rhumb Line Maps for technical support and hosting. John Meader Photography for technical support, and photo editing.

Partners for the Postcards from Gus blog:

Endnotes and Works Consulted:

1. Annie Proulx, Postcards, (Simon and Schuster, 1993), p.77.

2. Peter Zumthor, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion dedication, May, 2011.

3. Betsy Hewlett, “From the Preserve Archives: Charles Savage’s artistic vision for the gardens,” Preserve Perspectives, Land and Garden Preserve, June 15, 2021.

4. Rose Ruze, Savage Genealogy, Ancestors and Descendants of Augustus Chase Savage and Emily Manchester of Northeast Harbor, Maine (Concord, Massachusetts, 2005), p.31.

5. Asticou Terraces, Thuya Lodge, trails, historical and current information on Land and Garden Preserve properties: Land and Garden Preserve website, https://www.gardenpreserve.org/.

6. Emily Phillips’ diary entry: Savage Genealogy, pp.102-103.

7. Author’s knowledge, and good references for this history: Letitia S. Baldwin, Thuya Garden, Asticou Terraces & Thuya Lodge (Mount Desert Land and Garden Preserve, 2008) and G.W. Helfrich and Gladys O”Neil, Lost Bar Harbor (Camden, Maine, Down East Books, 1982).

8. Docents’ memories: Conversations with author’s mother Cecelia Phillips, Peggy Simpson (2018-2019), current and retired docents (2019-2021).

9. Hand-colored glass lantern slide by Frances Benjamin Johnston, photographer. "Reef Point," Beatrix Jones Farrand house, Bar Harbor, Maine. Pathway. Maine Bar Harbor, 1920. [Summer] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2008675993/.

10. Hand-colored glass lantern slide by Frances Benjamin Johnston, photographer. "Reef Point," Beatrix Jones Farrand house, Bar Harbor, Maine. Pathway to house. Maine Bar Harbor, 1920. [Summer] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2008675995/.

11. Portrait of Beatrix Farrand, Farrand (Beatrix J.) Collection, UC Berkeley, Environmental Design Archives, Calisphere, date of access: February 7 2022 16:57. Permalink: https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/28722/bk0010w428g/.

12. Regina Cole-Globe Correspondent, “How dedicated horticulturalists rescued the plantings of a legendary landscape to create two public gardens,” Design New England, Boston Globe, August 14, 2017, http://realestate.boston.com/design-new-england/2017/08/14/dedicated-horticulturists-rescued-plantings-legendary-landscape-create-two-public-gardens/.

13. Charles Kenneth Savage, Northeast Harbor, ca. 1949, Item 81087, Mount Desert Island Historical Society, 353 Sound Drive, Mount Desert, ME. https://www.mainememory.net/artifact/81087.

14. Augustus Phillips, handwritten entries in personal notebooks, collection of the author.

15. Images of Gus in his workshop, Asticou Inn, Phillips House, collection of the author.

16. Image from Bar Harbor Historical Society Exhibit: tour and interview with Deborah Dyer, Historian, Bar Harbor Historical Society, June 15, 2021.

17. Margaret Coffin Brown, Pathmakers: Cultural Landscape Report For The Historic Hiking Trail System Of Mount Desert Island (Boston, Massachusetts, Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, National Park Service, 2006) pp. 156-158.

18. Visitation Numbers (U.S. National Park Service), accessed December, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/visitation-numbers.htm.

19. Postcards: The Anchorage in the 1960s https://www.cardcow.com/762215/bar-harbor-maine-anchorage-motel/, The National Park Motel in the 1960s https://www.cardcow.com/574159/national-park-motel-bar-harbor-maine/.

Further Reading and Viewing

Baldwin, Letitia. Thuya Garden, Asticou Terraces, and Thuya Lodge. Mount Desert Land and Garden Preserve, 2008.

Brown, Margaret. Pathmakers: Cultural Landscape Report For The Historic Hiking Trail System Of Mount Desert Island. Boston,

Massachusetts: Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, National Park Service, 2006.

Cole, Regina. “How dedicated horticulturalists rescued the plantings of a legendary landscape to create two public gardens.” Design New England, Boston Globe. August 14, 2017.

Curtis, Joseph. Life of Campestris ulm, the oldest resident of Boston Common. Boston, Massachusetts: W.B. Clarke, 1910.

Dyer, Deborah. Bar Harbor: A Town Almost Lost: A Pictorial Essay of Bar Harbor’s Mansions Before and After the Fire of 1947. Unidentified publisher, 2008.

Helfrich, G. and Gladys O’Neil. Lost Bar Harbor. Camden, Maine: Down East Books, 1982.

Morison, Samuel. The Story of Mount Desert Island. Frenchboro, Maine: Islandport Press, 2001.

“Preserve Perspectives.” Land and Garden Preserve, September 2020 to present (and continuing). Articles and videos, including a video docent-led tour of Thuya Lodge.

Proulx, E. Annie. Postcards. New York, New York: Collier Books, 1993.

Schmitt, Catherine. Historic Acadia National Park. The Stories Behind One of America’s Great Treasures. Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press, 2016.

Tankard, Judith. Beatrix Farrand. Private Gardens, Public Landscapes. New York, New York: The Monacelli Press, 2009.

Zumthor, Peter. Atmospheres: Architectural Environments. Surrounding Objects. Birkhauser Architecture, 2006.