Ep. #04, The Confessions

Jack Pokorny

Podcast Copyright © 2021 by Keith Reeves, Jack Pokorny, and Margaret O’Neil. All Rights Reserved. Executive Producers: Keith Reeves and Maggie O’Neil. Producer: Jack Pokorny. Narrated and Written by Jack Pokorny. Original Music by Hee Won Park and Tommy Neil. Sandbox Atlas Blog Content Editors: Ben Meader and Emily Meader. Based on the meticulously researched book, The Case That Shocked the Country: The Unquiet Deaths of Vida Robare and Alexander McClay Williams by Samuel Michael Lemon, Ed.D. (2017). The podcast was generously supported by the Lang Center for Civic and Social Responsibility and the Program on Urban Inequality and Incarceration, both at Swarthmore College; the Swarthmore Black Alumni Network (SBAN); Keller, Lisgar & Williams, LLP. The producers wish to especially acknowledge the invaluable contributions of: Mrs. Susie Carter (Alexander’s sole surviving sibling); Dr. Sam Lemon (the great-grandson of Alexander’s original attorney); Teresa Smithers (a descendant of Fred Robare, Vida Robare’s husband); Osceola Perdue (Alexander’s great-niece) and her family; Attorney Robert C. Keller; Chris Rhoads; Sean Kelley, Annie Anderson, and Sally Elk, all of Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site in Philadelphia.

[ 22 min read, 33 minute listen ]

[0:33] Two days after delivering his first confession to Major Hickman, the superintendent at Glen Mills—and then a shorter one to the two detectives on the case on October 7th—Alexander is taken to the county jail. Not long after arriving, he is removed from his cell on the orders of Mr. McCarter on October 9th, despite the fact that a magistrate had ordered that he only be taken out for the purposes of attending a hearing. Nevertheless, the prosecution on the case illegally extracted Alexander to get yet another confession, this one being his third. Alexander did not have a lawyer present when he was taken from his jail cell.

The third confession, read by Alexander’s great-great-great-nephew, has some explicit content about sexual assault, that I’d like to warn some listeners about. This is Alexander’s most damning confession. [See footnote ^A]

Alexander Williams confession was the headline news of the Tyrone Daily Herald in Tyrone, Pennsylvania.

At the county building, Media, Delaware County, PA in the offices of the district attorney of Delaware County, Pennsylvania. October 9th 1930 at 12 o'clock noon. [By Mr. McCarter]: Alexander when you saw me yesterday you told me you wanted to correct the statement which you made on the other night, last night, out at Glen Mills. And you wanted to tell the whole truth and certain things you said in this statement were not correct. Is that a fact?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: Do you still desire to tell me what you told me yesterday?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: Now Alexander, were you in Cottage Number Five at Glen Mills?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: On last Friday, October 3rd 1930?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: Why did you first go into that cottage?[Williams]: To get some shoe polish.[Mr. McCarter]: Where were the cans of shoe polish kept?[Williams]: In the cupboard in the assembly room or dining room.[Mr. McCarter]: Was that cupboard kept locked?[Williams]: Sometimes.[Mr. McCarter]: Did you have any right to go in the cottage?[Williams]: No sir.[Mr. McCarter]: Did you go in to steal the boxes of shoe polish?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: Now after you went to the cottage, what did you do then?[Williams]: I went from the front house door to the kitchen.[Mr. McCarter]: What did you get in the kitchen?[Williams]: That knife sharpener.[Mr. McCarter]: This knife sharpener which I show you?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: Where did you get that from?[Williams]: Out of the kitchen drawer.[Mr. McCarter]: After you got the knife sharpener, what did you do?[Williams]: I came to the cupboard and tried to open it.[Mr. McCarter]: You mean that you tried to force the lock to get the cupboard open?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: And did you get it open?[Williams]: No sir.[Mr. McCarter]: What did you do then?[Williams]: I heard somebody. Mrs. Robare was walking around.[Mr. McCarter]: When you heard Mrs. Robare upstairs walking around, what did you do then?[Williams]: I went out in the kitchen and took the knife sharpener back and put it in place, and then I came back. And the ice pick was on the second table from the end. I took it and went tipping upstairs.[Mr. McCarter]: Was it when you heard her upstairs, that made up your mind that you will go upstairs?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: Why were you going upstairs?[Williams]: Going upstairs to ask her for a piece.[Mr. McCarter]: What do you mean by that?[Williams]: Screw her.[Mr. McCarter]: Why did you take the ice pick with you?[Williams]: So if she says she was going to tell, I will kill her.[Mr. McCarter]: You say that [you] tip-toed upstairs?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: Why did you do that?[Williams]: So she wouldn’t hear me coming.[Mr. McCarter]: Now when you got up to the door of her bedroom, was the door open or closed?[Williams]: It was open about two inches.[Mr. McCarter]: And what did you do then?[Williams]: I pushed the door open and went in.[Mr. McCarter]: Where was Mrs. Robare then?[Williams]: Standing near the dresser, combing her hair.[Mr. McCarter]: How was she dressed?[Williams]: She had a shirt and a pair of drawers.[Mr. McCarter]: When you told me before that you didn't know how she was dressed, you weren’t telling me the truth were you?[Williams]: No sir.[Mr. McCarter]: And when you told me in the previous statement, that you went upstairs to get the shoe polish, were you telling the truth then, as to that?[Williams]: No sir.[Mr. McCarter]: Now when you pushed open the door, where did you have the ice pick?[Williams]: In my overalls.[Mr. McCarter]: What did you say to her, and what did she say to you?[Williams]: She asked me what I wanted.[Mr. McCarter]: What did you say?[Williams]: Then I told her I wanted a piece.[Mr. McCarter]: Do you mean that you wanted to have intercourse with her?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: And when you told her what you wanted, what did she say?[Williams]: She said, “No. Go out!”[Mr. McCarter]: What did you do then?[Williams]: I just stood there, and when she started to fight with me—[Mr. McCarter]: You said she started to fight with you. What did she say?[Williams]: She grabbed me and tried to put me out.[Mr. McCarter]: What did you do then?[Williams]: I stabbed her twice in the arm.[Mr. McCarter]: When it was that you first pulled out the ice pick of your overalls?[Williams]: When she started to fight with me.[Mr. McCarter]: When you stabbed her in the arm, how many times did you stab her?[Williams]: Twice is all I know.[Mr. McCarter]: Where did that happen in the room?[Williams]: Right before the—I don't know what you call it, wardrobe or something.[Mr. McCarter]: You mean the closet where they kept the clothes?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: After you stabbed her with the ice pick in the arm, then what happened?[Williams]: She told me not to stab her anymore. She would give me some money and clothes.[Mr. McCarter]: And what did you do then?[Williams]: Then I shoved her over the bed.[Mr. McCarter]: What part of the bed did you shove her over?[Williams]: Bottom of the bed. The foot of it.[Mr. McCarter]: As you shoved her over the foot of the bed, what did you do, if anything?[Williams]: I kneeled on the bed.[Mr. McCarter]: Is that when you shoved her over the foot of the bed?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: What did you do when you kneeled on the bed?[Williams]: I was getting ready to perform.[Mr. McCarter]: When did you open your fly of your trousers?[Williams]: When I got to the top of the steps.[Mr. McCarter]: Before you went into the room?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: Now, were you going to perform and kneeling on the bed—what did she say?[Williams]: She started to groan.[Mr. McCarter]: What did you then do?[Williams]: I stabbed her 20 or 25 times.[Mr. McCarter]: Why did you stab her at that time?[Williams]: I was afraid she was going to tell.[Mr. McCarter]: Then what happened?[Williams]: Then I heard somebody walking along the walk. So I stabbed her two hard times. Then I went out and took the keys with me.[Mr. McCarter]: Did you do anything when you heard someone walking along the walk outside of the cottage?[Williams]: Yes. I took her bloomers off and wiped her breasts off so I wouldn’t get my hands printed.[Mr. McCarter]: Why did you think that would get your handprint?[Williams]: Where I stabbed her or her breast, blood was all over my hand.[Mr. McCarter]: Had your hand touched her body or breast?[Williams]: Yes. Right when I stabbed her it went deep in.[Mr. McCarter]: When you say this part of your hand, you are pointing to the bottom part of your hand?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: Do you mean that you drove the pick so deep that it went clear up to the hilt of the ice pick and your hand touched her?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: What did you do with the bloomers?[Williams]: I left them down by her foot.[Mr. McCarter]: Where were the keys in that room?[Williams]: On the dresser.[Mr. McCarter]: Did you take the keys?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: Why did you take the keys?[Williams]: To open the dormitory door.[Mr. McCarter]: Why did you need to open the dormitory door?[Williams]: To keep anyone from seeing me go out the front way, I didn’t want to go out that way.[Mr. McCarter]: Was the dormitory door locked?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: After you opened the dormitory door, where did you go?[Williams]: Through the dormitory and down the fire escape and to the basement.[Mr. McCarter]: And when you left which door did you go out?[Williams]: The basement door.[Mr. McCarter]: In your previous statement, you told me Alexander, you told me that you didn't know that Mrs. Robare was upstairs until you pushed the door open. Was that correct or not?[Williams]: Not correct.[Mr. McCarter]: Alexander when you lived in cottage number five, Mrs. Robare had reported you, hadn't she? For certain violations sent in reports?[Williams]: Not as I know of.[Mr. McCarter]: Did you get any blood on you from her?[Williams]: I got some on my hat—a little on my hat, on my pants and on my two thumbs.[Mr. McCarter]: How did you get the blood on your hat?[Williams]: When I went out the door, my hat dropped on the bed. When I went out the door I looked at it and it had blood on it.[Mr. McCarter]: When your hat dropped off your head, where did it drop?[Williams]: It dropped on the bed.[Mr. McCarter]: Was there blood on the bed?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: Did you do anything to get the blood off, or attempt to get the blood off your hat?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: What did you do?[Williams]: I washed it.[Mr. McCarter]: Where did you wash your hat?[Williams]: When I went to the cottage.[Mr. McCarter]: Which cottage?[Williams]: Cottage three.[Mr. McCarter]: How is it you didn’t get more blood on you as you stabbed her?[Williams]: I don't know sir.[Mr. McCarter]: Is what you have told me now, Alexander, the real truth about this?[Williams]: Yes.[Mr. McCarter]: Was Mrs. Robare dead when you pulled the bloomers off of her Alexander?[Williams]: No sir, she was lying on the bed groaning.[Mr. McCarter]: That's all.

Photo of Alexander Williams between McCarter and Major Hickman. Behind him are possibly the detectives on the case.

[9:25] It’s hard to imagine him saying these things, the small kid who ran away from the school to his parents not so long before this. It’s hard to believe that he would say that stuff about a woman who would protect him against her husband's beatings, even though he would hit her for defending him.

I think there is truth buried somewhere in the mess of these forced confessions. Was Alexander in cottage five on the day Vida was killed? I think he probably was, in a very ill-fated attempt to steal shoe polish. But did he go up to Vida’s room for the keys, like he originally said? It’s hard to say. Where does the truth fall in the smattering of possible realities laid out here? Is it in the contradictions that we can eliminate impossibilities, like a list to be checked off? Or will that cause us to miss something, to write off the truth prematurely.

Major Hickman was the superintendent of the school during Alexander’s time there. And it appears that he was largely responsible for Alexander’s arrest, so it makes sense for us to start at the beginning of his involvement to try and parse out what Alexander actually did on that day and how he eventually came to giving these two damning confessions.

Hansen B. Hickman sworn. [By Mr. McCarter] [By Mr. Ridley]: May I have the witness name please?[Maj. Hickman]: Hansen B. Hickman.[Mr. McCarter]: Now Major, when was your attention first called to the commission of this homicide?[Maj. Hickman]: About 8:00 in the morning on October 4th. The first notice I received of it, was the headline in the paper in Dayton, Ohio.[Mr. McCarter]: October 4th, Major, 1930?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir.[Mr. McCarter]: And where were you?[Maj. Hickman]: At Dayton, Ohio.[Mr. McCarter]: You came home?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir.[Mr. McCarter]: What time did you arrive at this institution?[Maj. Hickman]: About five o'clock on Sunday morning, October 5th.[Mr. McCarter]: Now superintendent of the institution Dr.—I mean Major, I apologize to you, I mean Major—what did you do?[Maj. Hickman]: The first thing I did was to send for the assistant superintendent and ask him to give me a complete account of what had occurred and what had been done to discover the perpetrator.[Mr. McCarter]: Now in the course of your investigation did you have a spirit of elimination? Did you investigate all the inmates?[Maj. Hickman]: What we did was to prepare elimination lists. Eliminate all boys who had been under direct supervision the entire afternoon of October 3rd.[Mr. McCarter]: How many boys did you find in that class that had been under supervision of the superintendent, and how many had been absent some time during the day?[Maj. Hickman]: Possibly as many as nine or ten, I wouldn't remember the exact number.[Mr. McCarter]: Nine or ten, all right, then what did you do?[Mr. Ridley]: Just a moment—[Mr. McCarter]: I withdraw that. Did you interview all the inmates who had been absent from their overseers?[Maj. Hickman]: I did not personally interview more than about five because the others had previously been interviewed either by the detectives or the district attorney.[Mr. McCarter]: All right. Well in the spirit of elimination, you eliminated everyone—save the defendant?[Maj. Hickman]: Save the defendant?[Mr. McCarter]: Excepting the defendant.[Maj. Hickman]: I wouldn't say—no.[Mr. McCarter]: What do you say?[Maj. Hickman]: I had not eliminated anyone so far as I was concerned until after I felt convinced of the guilt of the defendant.[Mr. McCarter]: Now, did you at any time, and in whose presence, have any conversation with the defendant Williams concerning this homicide which took place?[Maj. Hickman]: I did.[Mr. McCarter]: When was that, Major, as far as you can recall?[Maj. Hickman]: On Monday night, October 6th, about 11 o'clock, as I remember.[Mr. McCarter]: And who was present at the time?[Maj. Hickman]: Mr. Fox, the two detectives, Mr. Trestrall, and Mr. Smith and the District Attorney.[Mr. McCarter]: By Mr. Fox, that is Mr. Charles E. Fox?[Maj. Hickman]: Mr. Charles Edwin Fox of Philadelphia.[Mr. McCarter]: Former District Attorney of Philadelphia?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir.[Mr. McCarter]: He was a trustee at the institution?[Maj. Hickman]: He is chairman of the board.

Charles Edwin Fox

Charles Edwin Fox was born in Meadville, PA in 1882. He was a prominent figure in Philadelphia, being admitted to the bar in 1903 and elected as the District Attorney of Philadelphia in 1926. He later became the chairman of the board of Glen Mill School for Boys.

(Photo from the Philadelphia Jewish Exponant 1/15/1926)

[Mr. McCarter]: Can you tell me what was said Major, and what he said at that time?[Maj. Hickman]: I can't give the exact language, I can get the gist of it. He [Alexander] was asked if he was sent on an errand, to which he replied that he was sent on an errand, after tools with another boy. He told the route that he followed in going to get the tools and the route that he followed on the return. He also told about making a second trip to take a receipt to Mr. Hughes, the tool room officer, and I asked the route that he followed on that trip. But he denied that he had entered cottage number five, on that afternoon.[Mr. McCarter]: Did he deny that he knew anything about this affair?[Maj. Hickman]: He said he knew nothing.[Mr. McCarter]: Subsequent, Major, to that interview with him, was he later interviewed?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir.[Mr. McCarter]: And when was that?[Maj. Hickman]: About four o'clock on the afternoon of October 7.[Mr. McCarter]: And were you present at that time?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir, I interviewed him personally.[Mr. McCarter]: Now will you just tell us the conversation?[Maj. Hickman]: I brought him into my residence, the sitting room of my residence, where I questioned him again concerning his actions on the afternoon of October 3rd. In questioning him, I noticed that he changed the route which he was following according to his previous statement which made me rather suspicious. I was also suspicious because I had received definite information—Mr. Ridley interjects.[Mr. Ridley]: Now that is objected to. May it please the court.[By the Court]: Objection sustained.[Mr. McCarter]: In pursuance, Major, of what made you suspicious, then go on. You can't tell us why.[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir. I questioned him at length about what he did on the afternoon of October 3rd concerning his trip to the tools and his return with the tools. I finally got him to make statements which are exactly the opposite in character. And he finally reached the point where he denied that he had made more than one trip away from his force that afternoon.[Mr. Ridley]: May it please the court, I object him saying he denied, I want to know as nearly as I can, or as he is able to give it, what he said.[The Court]: What did he say?[Maj. Hickman]: I said, 'Alexander you have been lying as your statements do not agree.' He said, 'That is right. I have been lying.' Then I told him—made a statement to him—which wasn't exactly backed with facts, but backed with what I believed to be the fact.[Mr. Ridley]: That is objected to, may it please the court.[The Court]: All right.[Mr. McCarter]: In pursuance of what you did. What did you say, Major? We might as well have the whole thing.[Maj. Hickman]: I said, 'You were questioned the other night by strangers, but now you're being questioned by me. You should wonder why out of all these boys in this institution, that you were selected to be questioned. You were selected because we know the facts. You were seen in cottage number five.' He denied it.[Mr. McCarter]: What did he say major?[Maj. Hickman]: He said, 'I was not in cottage five on the afternoon of October 3rd,' but he changed the statement on being asked additional questions and said, 'I did go into cottage five to steal some shoe polish which I promised one of the other boys in the cottage.' He was then asked the question as to whether he had heard any noises while he was in the cottage. He stated, 'I did hear noises upstairs and heard someone say, "Did you get your hat?" ' I said, 'What door? What door did you leave by?' He replied, 'I left by the cottage front door.' I asked him the question as to whether he saw anyone after left the cottage. He said, 'I did, I saw two men, two colored men,' and in his reply described at length their dress. I then felt certain—[Mr. Ridley]: That is objected to![Mr. McCarter]: You can't tell us that, but in view of what he said he told you, these different stories—then what did you do Major?[Maj. Hickman]: I left him in the office in my sitting room, and I went to my office where I found Mr. Butler and told him what I'd learned.[Mr. McCarter]: Now how soon after that did you have any conversations or further conversations with Williams?[Maj. Hickman]: About 10 minutes after. I passed through the room in which I had left Alexander Williams and I told him, I said to him, 'I am not going to question you any further at this time. Later someone else will question you concerning this. I know that you are guilty. I'm going to leave you now.' Alexander said, 'Are you going away?' I said, 'No, I will be upstairs.' He said, 'Is Mr. Welch going away?' I said, 'No, he will be here with you and if you want me you can send for me.' I then left the room and went upstairs where I ate a cold lunch. [See footnote ^B][Mr. McCarter]: And how soon did you next see Williams?[Maj. Hickman]: About—I would say—in about 20 minutes. Mr. Welch called me from the stairway and I came down. Alexander was sitting on the settee with his head in his hands. I walked over to him and put my hand on his shoulder and he sobbed out the story to me.[Mr. McCarter]: What did Williams say to you when you said he sobbed out his story? Just tell us what he told you at that time.[Maj Hickman]: He said, 'I did it.' And I ask the questions, 'What did you do with the carpenters dividers?' He said, 'I did not do it with the carpenter dividers. I did it with an ice pick.' - Sam Lemon

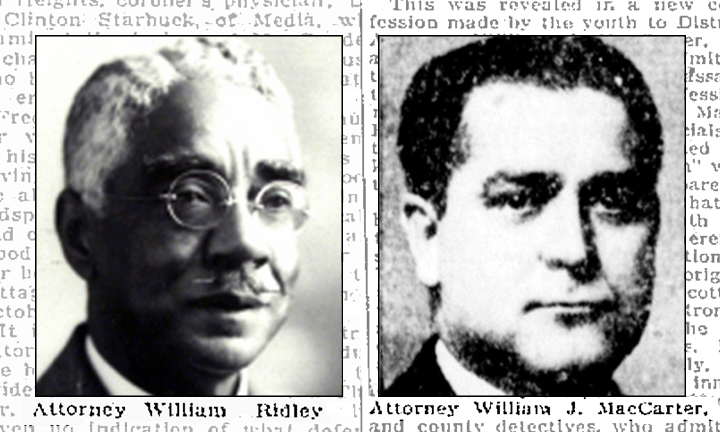

William Ridley (left), Alexander’s defense attorney and William McCarter (right) the prosecution.

(Ridley photo was provided by Sam Lemon. McCarter image is from the Chester Times, 10/21/1931)

[18:50] Alexander’s confessions, as if not enough on their own, are fortified by Major Hickman’s testimony. He paints the picture of Alexander confused and scared, at first adamant that he knew nothing of the crime before completely breaking down and admitting his horrifying and surprising involvement in her death. And there was the Major, at once a piercing force of authority puzzling out the truth and a comforting presence.

But thinking back over Hickman’s testimony, it’s simply wrong, even perverse, that of all the boys, he told Alexander he knew he did it. Why did Hickman believe Alexander had killed Vida? He had yet to even eliminate anyone else as a potential suspect before jumping to that conclusion. Alexander was a kid that may have had a learning disability, who may have been addicted to huffing shoe polish, who had been at the institution for a very long time. And he was being told by the people in the highest authority that he killed Vida. In the end, he told them what they wanted.

Yet how did they get to that point? What was the environment at Glen Mills like, and why was it that Alexander was for four years in the custody of a man who abused him? Here is Mr. McCarter questioning Major Hickman about the policy of punishment at Glen Mills.

[Mr. McCarter]: Now, the boys of this kind are sent to the institution at 14 years of age. How long do you keep them there?[Maj. Hickman]:That depends entirely on the conduct of the individual boy.[Mr. McCarter]: Well if a boy was a good boy at 14 years of age, how long would you keep him?[Maj. Hickman]: He would be able to earn his parole in a minimum period of 18 months.[Mr. McCarter]: Say this boy came when he was 14, and if he is 18 now, he has been an inmate at your institution for four years?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir, somewhat more than four years.[Mr. McCarter]: What was the charge against him?[Maj. Hickman]: The charge against him was delinquency. The specific charge, according to the records, was arson.[Mr. McCarter]: That is, burning a barn or burning a house?[Maj. Hickman]: Burning a barn as I remember it.[Mr. McCarter]: Burning a barn—Doctor or Major—if a boy's unruly, what form of punishment does he undergo? What do you do to him?[Maj. Hickman]: It depends entirely on the seriousness of the offense for which he committed. The officer, in whose charge the boy is working at the time he commits an offense, makes a written report of the offense which is presented the following morning at the Summary Court held every morning except Sunday. He is given a hearing and if the offense is a minor offense, he may receive a suspended sentence. He may receive demerits which will lengthen his stay at the institution. If it is a serious crime, he might be given corporal punishment. [see footnote ^C][Mr. McCarter]: I didn’t get the last, Major.[Maj. Hickman]: If it is a serious crime, he might be given corporal punishment.[Mr. McCarter]: What do you mean by corporal punishment?[Maj. Hickman]: I mean punishment with a strap.

A strap similar to this would have been used for corporal punishment at Glen Mills school in the 1930s. Seen here is leather school strap circa 1920, part of the Victorian Collections at the Federation University Australia Historical Collection.

[Mr. McCarter]: You mean in Glen Mills, a reform school, that you strap the inmates?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes, when absolutely necessary we do, amounting to possibly six to seven times a month.[Mr. McCarter]: What offense could they commit that would warrant the strapping you talk about?[Maj. Hickman]: One of the offenses is escaping from the institution.[Mr. McCarter]: What other offenses?[Maj. Hickman]: Offenses such as sodomy, breaking and entering.[Mr. McCarter]: What other offenses?[Maj. Hickman]: There are no set list of offenses, it depends on the individual act.[By Mr. McCarter]: Now this boy you say, in due course, if he had been a good boy, he could've been liberated in 18 months.[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir.[Mr. McCarter]: And why wasn't he liberated in 18 months?[Maj. Hickman]: Because he had a very bad record.[Mr. McCarter]: Now tell me Major, his record.[Maj. Hickman]: I couldn't give you the individual offenses that he committed. Those were part of the records turned over to the district attorney.[By Mr. McCarter]: Well, was his record so bad you ever had to strap him?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes, on at least one occasion and possibly two.[By Mr. McCarter]: You strap this boy at Glen Mills upon more than one occasion while he was an inmate?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir.[Mr. McCarter]: Between the age of 14 and 18?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir.[Mr. McCarter]: Now who did the strapping?[Maj. Hickman]: I wouldn't absolutely be sure, but I'm sure it was at least on one occasion, handled by the military director who now sits in the Summary Court.[Mr. McCarter]: The military director did the strapping. Who supervises the strapping?[Maj. Hickman]: I do.[By Mr. McCarter]: How many lashes do you give them?[Maj. Hickman]: Depending on the severity of the offense, it might be 15 and it might be 18.[Mr. McCarter]: What kind of strap do you use?[Maj. Hickman]: A light leather strap.[Mr. McCarter]: So, you take a light leather strap with a military director, a big hard physical man, and strap a youth 14 or 15 years of age 15 times or more, would you?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir.[Mr. McCarter]: Well, when you found an inmate was incorrigible, why didn't you transfer him to some other institution where they would have better supervision over him?[Maj. Hickman]: We cannot transfer. We don't have the authority to transfer boys.[Mr. McCarter]: So it doesn't make any difference what a boy does there, you have to keep him there?[Maj. Hickman]: Unless we should approach the judge on the matter and the judge might take action.[Mr. McCarter]: If this boy was incorrigible, so much so that you had to give him a severe beating, why didn't you transfer him to an institution where they would have better supervision over him?[Maj. Hickman]: That would be a question for the court. I don't know whether or not it would be possible for a court to transfer a boy that was committed at the age of 14 on arson or not.[Mr. McCarter]: The court wouldn't know anything about it until you complained to the court.[Maj. Hickman]: Not likely so.[By Mr. McCarter]: You never made any complaint to the court about this boy being incorrigible?[Maj. Hickman]: No.[Mr. McCarter]: But you gave him a summary punishment set aside for boys who are incorrigible there.[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir.[Mr. McCarter]: In other words you had a whipping post.[Maj. Hickman]: No. We don't have a whipping post.[Mr. McCarter]: I mean figuratively speaking you administered punishment to them.[Maj. Hickman]: Yes sir. - Sam Lemon

[25:04] After hearing Major Hickman’s testimony about Alexander’s bad record, Mr. Ridley found and entered the penal record into the evidence of the summary court, requesting Major Hickman read out the entire list of punishments administered to Alexander.

[Maj. Hickman]: October 14, 1926: Careless work. Reprimand.[Mr. McCarter]: In other words, reprimand—he was spoken to?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes, he was spoken to. November 24, 1926: Disobedient. 20 demerits. April 5, 1927: Licentiousness. Suspended.[Mr. McCarter]: What do you mean by that Major?[Maj. Hickman]: In this case I presume he was accused of some vulgar act or something of that kind. I don't know what it might have covered, but evidently the evidence was not strong enough against him and it was suspended. September 27, 1929: Malicious mischief. 40 demerits. January 30, 1930: Insolence. 40 demerits. March 27, 1930: Theft and malicious destruction of property. 200 demerits. June 11, 1930: Licentiousness. 80 demerits.[Mr. McCarter]: Yes. Major, I show you two papers, marked 26 and 27. Are they part of the records of Glen Mills School covering particularly the two offenses of licentiousness?[Maj. Hickman]: They are.[Mr. McCarter]: From those records can you tell us what the defendant Williams had done so he that was charged with licentiousness on those two occasions?[Maj. Hickman]: The record shows that on April 5, 1927 he was charged with the offense of sodomy. The record of June 11, 1930 shows that he was charged with the offense of attempting to commit sodomy.[Mr. McCarter]: Where did that occur?[Maj. Hickman]: In the barn, in the loft of the barn.[Mr. McCarter]: And with whom was that committed, the sodomy, on each occasion?[Maj. Hickman]: The record of June 11th does not show the name of the boy but it was another boy in the institution. The record of April 5th—[Mr. McCarter]: You needn’t give us a name.[Maj. Hickman]: But it was with boys in the institution.[Mr. McCarter]: I see. -Sam Lemon

In researching this case, I have never heard anyone talk about how Alexander was gay. And if he was, the only evidence that I have found that gives us a hint at his sexuality is this section of the transcript. Yet on two different dates, spread three years apart, Alexander was caught participating or attempting to participate in a sexual act with another boy in the institution. He was punished for doing so, physically beaten with a strap by Mr. Quinn, the military director, and just so happens a friend of Fred Robare, in the presence of Major Hickman.

When I mentioned this section of the trial transcript to someone, she told me about a book that explored the high rate of sex at all boys schools and suggested that this section may not have meant Alexander was actually gay, but perhaps he was only a product of his circumstances, his environment. I am not entirely convinced of that.

[28:10] The world of Alexander’s childhood was a world marked by injustice. It attempted to strip him of everything. Glen Mills, supposedly a reform school and the oldest in our nation, took from Alexander his autonomy and his family, forced him into daily manual labor reminiscent of chain gangs or slavery. He was discriminated against because of his age, because of his race, and as we have found out here, because of his sexuality. To the administrators at Glen Mills, he would have seemed the most vulnerable and target-able boy at the school. The boy who had been there the longest. The boy most susceptible to public disgust and to hate, to homophobia, and racism. Did Major Hickman believe Alexander was disposable? Who else might have come to that conclusion?

It’s worth sitting with the factual reality that the KKK was an ever present menace to the black community at the time, allowed to march and perform rituals openly in the very city Alexander’s trial was taking place. Oliver N. Smith (the chief county detective) and Michael Trestrall were both members of the Elks Club in Media, which was then largely made up of KKK members.

And yet, up until shortly before he was arrested, Alexander was not a product of his circumstances. He was a rebel, a thief, a boy without care for the consequences of his actions. A boy who burned barns possibly because of some childhood trauma. It’s not a matter of romanticizing his folly to say that Alexander was, for good or bad, his own person until he gave those confessions. The long list of demerits he received for speaking back, for stealing, for being himself, speaks to that. His is not a simple story, but a complex one, much like the real world and the progression of history. As much as other people have tried to tell his story for him, I hope some of the real Alexander is shining through all of this.

Campus of Glen Mills House of Refuge 1917. Photo from Lane Genealogy

Major Hickman’s testimony ends with Mr. Ridley wondering how many demerits Alexander had in total and when he would have been released if he had never been accused of killing Vida.

[Mr. Ridley]: Have you any idea how many demerits? Oh just guess at it, Major, a thousand?[Maj. Hickman]: I hardly think he had as many as a thousand.[Mr. Ridley]: In that neighborhood?[Maj. Hickman]: I wouldn't be able to say just how many.[Mr. Ridley]: Major, would he have been released?[Maj. Hickman]: Yes. If he had kept the same type of record he was keeping at the institution, he would have been released on age 21, if no other time.[Mr. Ridley]: Automatically he would have been released at 21 years of age?[Maj. Hickman]: Automatically.[Mr. Ridley]: That is all.[…]

[Sam Lemon]: A thousand demerits. It's almost like—can he ever get out of here?-Sam Lemon

Despite the force of Alexander’s confessions, there is still something to add, to further complicate his story. Next episode, we will hear from Teresa Smithers, a descendant of Fred Robare. Stay with us for Episode 5: The Verdict.

Footnotes:

A. On False Confessions: Alexander gave three separate confessions over the course of a few days. Though these confessions might seem damning, false confessions are not rare. The amount of mental exertion that a person undergoes, especially a child, during an interrogation, is immense. Juveniles are also prone to psychological manipulation especially when the subject is tired and traumatized. A younger person will often tell the authority figure what they want to hear, even if what they end up saying is detrimental to themselves. With the help of new technology and the use of DNA, we are now able to help exonerate those who were imprisoned over false confessions. Organizations such as the Innocence Project devote themselves to helping people who were wrongly convicted.

B. On Interrogation Tactics: One of Alexander’s confessions given was during the questioning of Glen Mills Superintendent, Major Hickman. Hickman, it seems was adept at deploying some of the tactics that are often used in police interrogation. In an interrogation setting, an officer is within his/her rights to make false statements in order to get a confession. This is to say that as long as what is being stated isn’t outlandish, investigators can claim or imply they have more evidence then they do. It is considered a reasonable psychological ploy to get the suspect to talk and explain what happened. This practice when utilized, has to be scrutinized closely as it can easily lead into coercion. Alexander would have little defense against these psychological tactics as a solitary 16-year-old without pre-trial legal council. Major Hickman told Alexander that he was being questioned because they already knew all the facts. He declared that he already knew Alexander was guilty—it is likely that this left no doubt to Alexander as to how the conversation would unfold.

C. On Corporal Punishment in Schools: Corporal punishment, or rather, the sanctioned punishment of another’s body, was regularly used in the 19th and 20th centuries in many school systems in the United States. Teachers, under the common law practice in loco parentis, could discipline students as if they were doing so in the place of the minor’s parents.

It wasn’t until 1977 in the case Ingraham v. Wright that federal law confronted corporal punishment. The case was about 14-year-old James Ingraham who had been restrained and paddled causing him to need medical attention. It was decided that the Constitution and its Amendments were not violated, but that those using corporal punishment should go by the precedent of “reasonable but not excessive” in their punishments. It was also decided that there would not be a federal law regarding corporal punishment—it would be decided state by state. By 1977 only four states had banned corporal punishment. Its use has been on the decline since that time (about 4% of students in the 1970s to less than 0.5% today). As of 2019, corporal punishment in schools is still legally allowed in 19 states, though frequency is geographically biased toward southern U.S. states.